Mari Selvaraj demonstrates a clear vision in his films, championing equality through his protagonists. However, it is the unique vantage point from which they wage their battles that sets each of his movies apart. Pariyan, an innocent do-gooder fights for his rights from the bottom up. Karnan, a more cognizant individual fights with a violent determination. And Maamannan, someone who seemingly has achieved “equality”, continues to fight for it by embracing new approaches, inspired by his son. Sprinkled with Mari’s quintessential metaphors, Maamannan carries the torch of his previous two movies.

The film opens with a contrast between two sons and their attitudes toward someone who has suffered defeat. Athiveeran advises his student to keep his head up – Yaaru jeikkaranga nu mukkiyam illa. Yaaru bayapdranga nu than mukkiyam. In contrast, Rathnavelu callously slaughters his dog. Athiveeran, scarred by his father’s silence during his traumatic childhood, becomes someone who never turns a blind eye to injustice. Rathnavelu idolizes his father’s heartless treatment of others, carrying on that legacy. Athiveeran cherishes his pigs, harbouring dreams of them growing wings and soaring across the world. Rathnavelu derives satisfaction from making his dogs participate in races, butchering them, and exploiting them as hunters. This contrasting journey persists until the film’s conclusion, where the sole surviving piglet finds solace in the care of the entire Maamannan family, while Rathnavelu futilely shoots the dogs pursuing him, realizing they persist regardless of his actions. The film masterfully portrays the involvement of different generations and their perceptions of the world.

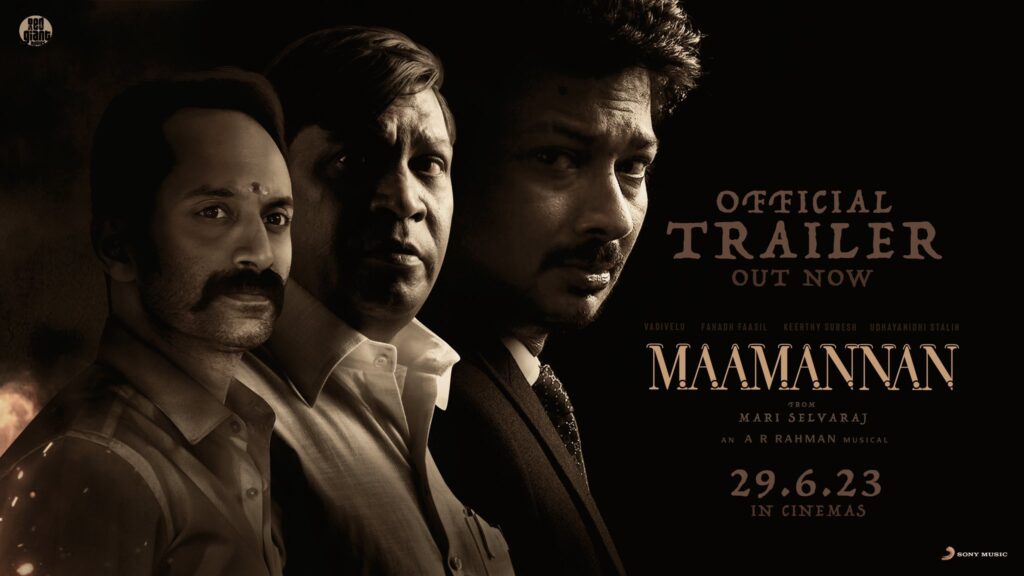

There is a brief black-and-white flashback that delves into the traumas experienced by Athiveeran and Maamannan – this 10-minute sequence alone is enough for the Vadivelu fan in me to celebrate this beast of an actor on screen. What a performance he delivers! Portraying a character who has achieved great heights yet remains unfulfilled, torn between educating those around him about equality, unable to even sit in front of his party leaders, and managing his defiant son with political maturity – pure class! His desperate cry during a political campaign to make his voice heard is a testament to his prowess. The theater erupted with applause when he kicked his way out of the fight during the interval block. I couldn’t contain my excitement when he pulls out his gun to silence Rathnavelu as he arrogantly prattles on about his pride. Fahad also delivers a stellar performance as the antagonist. Although his character lacks significant development, his portrayal of rage in various situations captivates us throughout the film.

Like his previous works, Mari fills Maamannan with animal symbolism and metaphorical parallels. However, this time it may have veered slightly toward excess. At times, it felt like a time loop of scenes, each reiterating the same message: Athiveeran and Maamannan face oppression, Athiveeran fights back, and Maamannan urges restraint. The scene where Athiveeran takes out his gun in a village seems entirely unnecessary, reminiscent of a misrepresented Chekhov’s gun. The final election victory fails to evoke the sense of triumph for Maamannan, especially considering the immense struggles endured during the campaign. Additionally, Athiveeran’s subsequent dialogue, explaining the metaphor of running dogs that arose in the previous scene, seems to excessively spoon-feed the audience, something that Mari’s very rarely does.

For someone who penned Jothi in Pariyerum Perumal, one of Tamil cinema’s most well-written female characters, witnessing Leela on screen donning the stereotypical checked shirt of a rebellious Tamil cinema heroine was profoundly disappointing. Apart from serving as a contrast, showcasing her fight for equality despite belonging to the same community as Rathnavelu, she fails to contribute substantially to the film. Rahman, with his impeccable timing, orchestrates the highs at the right moments and moves us with Utchanthala in multiple instances. However, the remaining background music and songs fail to make a lasting impression. It led me to ponder whether the choice of Rahman was truly fitting for this subject, especially considering Mari’s meticulousness in every aspect of his films.

I perceive Maamannan through two lenses: as a vehicle for educating the audience about oppression and as a technically proficient piece of art that stands the test of time. However, I wonder if it succeeds in fulfilling both objectives. While the film possesses brilliant frames, parallelisms, and metaphors on paper, I wonder if it overindulges in these elements. Perhaps a more restrained approach, focusing on forging a stronger emotional connection with the audience, could have been more effective. Nevertheless, Maamannan remains an experience that everyone should undertake, even if just for the stellar performances by Vadivelu and Fahad. They truly are legends on the screen!